Scala 公开课笔记

Coursera上的瑞士洛桑理工大学Scala函数式编程原理(Functional Programming Principles in Scala)课程笔记。

课程链接:Functional Programming Principles in Scala

Getting Started

Scala开发环境配置相关的几点经验:

- 解决Scala编译太慢的问题:使用sbt构建,保持一个运行sbt的console。也就是说,让一个JVM常驻内存,可以显著提升编译效率。

-

sbt解决依赖的过程中出现sha1 error: 在build.sbt中增加如下内容:

checksums in update := Nil或者在sbtconfig.txt中增加如下内容,禁用全局sha1 check:

-Dsbt.ivy.checksums="" # 默认值为"md5, sha1" -

自定义sbt的缓存位置: 在sbtconfig.txt中增加如下内容:

-Dsbt.ivy.home=d:/Java/sbt/ -Dsbt.boot.directory=d:/Java/sbt/boot/

Week 1: Functions & Evaluations

-

三种编程范式(Programming Paradigms)

- impreative programming

- functional programming

- logic programming

-

命令式编程受限于冯·诺依曼(Von Neumann)体系结构。

-

不可变类型理论(Theories without Mutation)

-

三个要点:将精力集中于定义运算符,最小化状态改变,将运算符视为函数。

-

REPL:Read-Eval-Print Loop

求值过程:从左至右求值,如果有函数,先从左至右对参数求值,再将参数的值带入。

带入模型(The substitution model)是在lambda演算中形式化,是Functional Programming的基础(foundation)。

终止问题:

def loop: Int = loop

这个求值过程永远不会终止。

The interpreter reduces function arguments to values before rewriting the function application.

- 三种求值策略(evaluation strategy):Call-by-Name, Call-by-Value, Call-by-Need

求值策略与Subsitution Model.

-

Call-by-value

Call-by-value has the advantage that it evaluates every function argument only once.

-

Call-by-name

Call-by-name has the advantage that a function argument is not evaluated if the corresponding parameter is unused in the evaluation of the function body.

-

Call-by-need

Call-by-need is a memoized version of call-by-name where, if the function argument is evaluated, that value is stored for subsequent uses. (Haskell)

由于两种求值策略的区别,某些求值序列可能在一种策略下会终止,在另外一种求值策略下并不会终止。

例如:

def loop(): Int = loop

def func(a:Int, b:Int) = 1

求值:

func(1, loop)

如果是CBV,参数的求值过程不会终止,而如果是CBN,只有在用到参数时才会对参数求值,因此这个求值过程会直接返回1,而不会对参数loop求值。

只有在以下情况下两种策略会返回相同的值:

the reduced expression consists of pure functions, and both evaluations terminate.

在Scala中,一般都是Call-by-Value, 如果函数的参数用=>来表示类型,那么该参数会是Call-by-Name。

例如:

def func(x: Int, y: => Int) = 1

对于这个函数定义,x是CBV,而y是CBN。func(1, loop)能够终止,因为并不需要对loop进行求值。

- 语句块和词法作用域(Blocks and Lexical Scope)

Scala允许函数嵌套。例如:

// Square roots with Newton’s method

def sqrt(x: Double) = {

def sqrtIter(guess: Double, x: Double): Double =

if (isGoodEnough(guess, x)) guess

else sqrtIter(improve(guess, x), x)

def improve(guess: Double, x: Double) =

(guess + x / guess) / 2

def isGoodEnough(guess: Double, x: Double) =

abs(square(guess) - x) < 0.001

sqrtIter(1.0, x)

}

Scala中的Block:

{

var x = f(3)

x*x

}

对于Block,Scala中变量和函数的可见性如下:

The definitions inside a block are only visible from within the block.

The definitions inside a block shadow definitions of the same names outside the block.

Definitions of outer blocks are visible inside a block unless they are shadowed.

- 尾递归(Tail Recursion)

Implementation Consideration: If a function calls itself as its last action, the function’s stack frame can be reused. This is called tail recursion.

在Scala中,只有对当前函数的直接递归调用能够被尾递归优化。使用@tailrec注解表明当前函数存在尾递归。如果对一个不是尾递归实现的函数使用@tailrec注解,将会产生错误。

@tailrec

def gcd(a:Int, b:Int): Int = {

if (b == 0) a else gcd(b, a % b)

}

// tail recursion version of factorial function.

def factorial(n: Int): Int = {

@tailrec

def factorial_i(acc: Int, n: Int): Int = {

if(n == 0) acc

else factorial_i(acc*n, n-1)

}

factorial_i(1, n)

}

// tail recursion version of Fibonacci sequence.

// NOTE: need two accumulator.

def fibonacci(n: Int, acc_first: Int, acc_second: Int): Int = {

if(n == 0) acc_first

else fibonacci(n-1, acc_second, acc_first + acc_second)

}

有这几个例子可以看到将满足一定条件的普通递归转化为尾递归的基本方法和技巧。

- Scala中,函数没有返回值时,默认返回

Unit。

Week 2: Higher Order Functions

- Functional languages treat functions as first-class values.

在Functional Programming中,函数可以被当成一个参数,也可以作为返回值。

高阶函数的定义:

Functions that take other functions as parameters or that return functions as results are called higher order functions.

使用高阶函数的例子:

def sum(f: Int=>Int, a: Int, b: Int) {

if(a > 0) 0

else f(a) + sum(f, a+1, b)

}

def id(x:Int): Int = x

def cube(x:Int): Int = x*x*x

def fact(x:Int): Int = if(x==1) 1 else x*fact(x-1)

def sumId(a, b) = sum(id, a, b)

def sumCube(a, b) = sum(cube, a, b)

def sumFact(a, b) = sum(fact, a, b)

-

在Scala中,函数也是一种类型。例如

Int=>Int表示的就是参数类型为一个Int, 返回值也是Int的函数的类型。 -

匿名函数(Anonymous Functions)

One can therefore say that anonymous functions are syntactic suger

另一种构造匿名函数方法:

{ def f(???) = ???; f }

例如:

List.range(0, 10).map({def f(a) = println(a+1); f})

等价于:

List.range(0, 10).map(a:Int => println(a+1))

- Functions Returning Functions

Scala中,函数可以将一个函数作为参数,也可以将一个函数作为返回值。如下例:

object progfun {

def sum(f: Int=>Int): (Int, Int) => Int = {

def sum_i(a:Int, b:Int): Int = {

if(a > b) 0

else f(a) + sum_i(a+1, b)

}

sum_i

} //> sum: (f: Int => Int)(Int, Int) => Int

sum(x => x*x*x)(1,3) //> res0: Int = 36

}

- Multiple Parameter Lists

Scala在定义函数时,可以有一个参数列表,也可以有多个参数列表。如下例:

def sum(f: Int => Int)(a: Int, b: Int): Int = {

if(a > b) 0 else f(a) + sum(f)(a+1, b)

} //> sum: (f: Int => Int)(a: Int, b: Int)Int

// application

sum(a => a*a*a)(2,4) //> res0: Int = 99

这也是Scala的一个语法糖(syntactic suger)的例子。

- Carrying

By repeating the process n times

def f(args1):::(argsn 1)(argsn) = E

is shown to be equivalent to

def f = (args1 ) (args2 ) :::(argsn ) E):::))

This style of definition and function application is called currying, named for its instigator, Haskell Brooks Curry (1900-1982), a twentieth century logician.

Conceptually, currying is a fairly simple idea. Wikipedia defines it as follows:

In computer science, currying, invented by Moses Schönfinkel and Gottlob Frege, is the technique of transforming a function that takes multiple arguments into a function that takes a single argument (the other arguments having been specified by the curry).

For example, in Scala, we can write:

def add(x: Int, y: Int) = x + y

add(1, 2) // 3

add(7, 3) // 10

And after currying:

def add(x: Int) = (y: Int) => x + y

add(1)(2) // 3

add(7)(3) // 10

You can also use the following syntax to define a curried function:

def add(x: Int)(y: Int) = x+y

add(1)(2)

add(7)(3)

使用Scala Function包中的uncurried函数可以得到一个函数的普通版本。例如:

def sum(a: Int)(b: Int) = a+b

def normalSum = Function.uncurried(sum)

println(sum(1)(2))

println(normalSum(1, 2))

-

Scala中的

=>是右结合。例如:Int => Int => Int

等价于:

Int => (Int => Int)

- 使用Currying来实现一个简单的mapReduce:

def mapReduce(f:Int=>Int,combine:(Int,Int)=>Int, zero:Int)(a:Int,b:Int):Int =

if(a > b) zero

else combine(f(a), mapReduce(f, combine, zero)(a+1, b))

上面的

def sum(f: Int => Int)(a: Int, b: Int): Int = {

if(a > b) 0 else f(a) + sum(f)(a+1, b)

}

可以改成mapReduce的写法:

def sum_mr(f: Int=>Int)(a: Int, b: Int): Int = mapReduce(f, (x, y)=>x+y, 0)(a, b)

-

在Scala中应该注意:一个函数能够找到(调用)定义在他下边的函数当且仅当这两个函数之间没有求值表达式。

-

Types in Scala

Scala中的几种数据类型:

- A numeric type: Int, Double, Float, Char, Byte, Long

- The Boolean type with the values true and false.

- The String type.

- A function type, like Int => Int, (Int, Int) => Int

- Class

Class可以用来定义新的数据类型。例如,使用Scala按照如下方式来定义分数:

class Rational(x: Int, y: Int) {

def numer = x

def denom = y

}

This definition introduces two entities:

- A new type, named Rational.

- A constructor Rational to create elements of this type.

- Object

We call the elements of a class type objects.

如何创建对象:

new Rational(1, 2)

- Methods

类的方法相关的示例:

class Rational(x: Int, y: Int) {

def numer = x

def denom = y

def add(that: Rational) =

new Rational(numer*that.denom + that.numer*denom,

denom*that.denom)

def neg: Rational = new Rational(-numer, -denom)

override def toString(): String = numer + "/" + denom

}

此处的toStirng方法是覆盖Object类的方法,因此,需要显式地加上一个override,否则将会出现编译错误。这个toString函数也可以简单地写成:

override def toString = numer + "/" + denom

这也体现出了Scala语言本身语法的灵活性。

- 值得注意的是,上述的Scala代码编译后得到的class文件反编译为java文件是这样的:

public class Rational

{

private final int x;

private final int y;

public int numer()

{

return this.x;

}

public int denom()

{

return this.y;

}

public Rational add(Rational that)

{

return new Rational(numer() * that.denom() + that.numer() * denom(),

denom() * that.denom());

}

public String toString()

{

return new StringBuilder().append(numer())

.append("/")

.append(BoxesRunTime.boxToInteger(denom()))

.toString();

}

}

另外,我发现

def gcd(a: Int, b: Int): Int = if(b == 0) a else gcd(b, a%b)

对应的java代码是这样的:

private int gcd(int a, int b)

{

for (;;)

{

if (b == 0) {

return a;

}

b = a % b;a = b;

}

}

可见,Scala编译器对于递归的优化做得相当不错。

-

Data Abstraction: This ability to choose different implementations of the data without affecting clients is called data abstraction.

-

Self Reference:Scala中也有与Java对应的this的概念和语法。

-

Preconditions: 定义类的构造方法的前置条件require

在上面的分数的例子中,分母不能为0,可以使用require来做一下限制:

class Rational(x: Int, y: Int) {

require(x != 0, "the denominator can't be zero.")

def numer = x

def denom = y

}

如果传入的参数y为0,将会产生一个IllegalArgumentException:

var t = new Rational(10, 0)

抛出异常:

java.lang.IllegalArgumentException: requirement failed: the denominator can't be zero.

关于require的详细解释如下:

require is a predefined function.

It takes a condition and an optional message string.

If the condition passed to require is false, an IllegalArgumentException is thrown with the given message string.

- Assertions

失败时同样是抛出一个java.lang.IllegalArgumentException。

二者的区别:

- require is used to enforce a precondition on the caller of a function.

- assert is used as to check the code of the function itself.

- 构造函数示例:

Scala中,直接使用this来定义构造函数。如下例:

def this(x: Int) = this(x, 1)

-

Scala的求值模型为实参替换形参的求值模型(based on substitution)。

-

操作符重载:

重载+, -, *, /, <, >

def + (r: Rational) = new Rational(numer*r.denom + r.numer*denom,

denom*r.denom)

重载负号(-)

符号是一个一元运算符(Unary operator):

def unary_- : Rational = new Rational(-numer, denom)

注意,-和:之间的空格不能省略,否则会导致编译器认为-:是一个运算符。

Week 3: Data and Abstraction

- Abstraction Classes, 抽象类。

Abstraction classes can contain members which are missing an implementations. No instance of an abstract class can be created with the operator new.

abstract class IntSet {

def incl(x: Int): IntSet

def contains(x: Int): Boolean

}

- Class Extensions

Scala中类支持继承,示例:

class Empty extends IntSet {

def incl(x: Int): IntSet = ???

def contains(x: Int): Boolean = ???

}

但,如果子类也是abstract修饰的,那么就可以不同实现父类的所有抽象方法。

- 直接定义object:全局唯一的类的实例(singleton object)。例如上面的例子里的

Empty类的实例都是相同的。可以写成:

object Empty extends IntSet {

def incl(x: Int): IntSet = new NonEmpty(x, Empty, Empty)

def contains(x: Int): Boolean = false

}

但是,使用object继承一个class时,这个class不能有未实现的方法。

这种object会在第一次引用时被创建,不能使用new来创建实例。

main函数:

object Hello {

def main(args: Array[String]) = println("hello scala.")

}

- Dynamic Binding

Object-oriented languages(including Scala) implement dynamic method dispatch. This means that the code invoked by a method call depends on the runtime type of the object that contains the method.

Dynamic dispatch of methods is analogous to calls to higher-order functions.

- Package

Scala中import的三种语法:

import A.func

import A.{func1, func2}

import a._ // 导入整个包里的所有内容

- Traits

In Java, as well as in Scala, a class can only have one superclass. But what if a class has several natural supertypes to which it conforms or from which it wants to inherit code? Here, you could use traits.

Wikipedia上关于Traits的解释:Trait_(computer_programming)。

A trait represents a collection of methods, that can be used to extend the functionality of a class.

Scala中实现trait的语法:

class A extends TA with TB with TC

表示类A继承并且实现了trait TA, TB, TC。多继承时,多个父级trait之间用with连接。

Traits不能有参数。Traits仅仅是一系列方法的集合。

Traits resemble interfaces in Java, but are more powerful because they can contains fields and concrete methods.

Traits中的方法可以有默认实现(default implementations)。

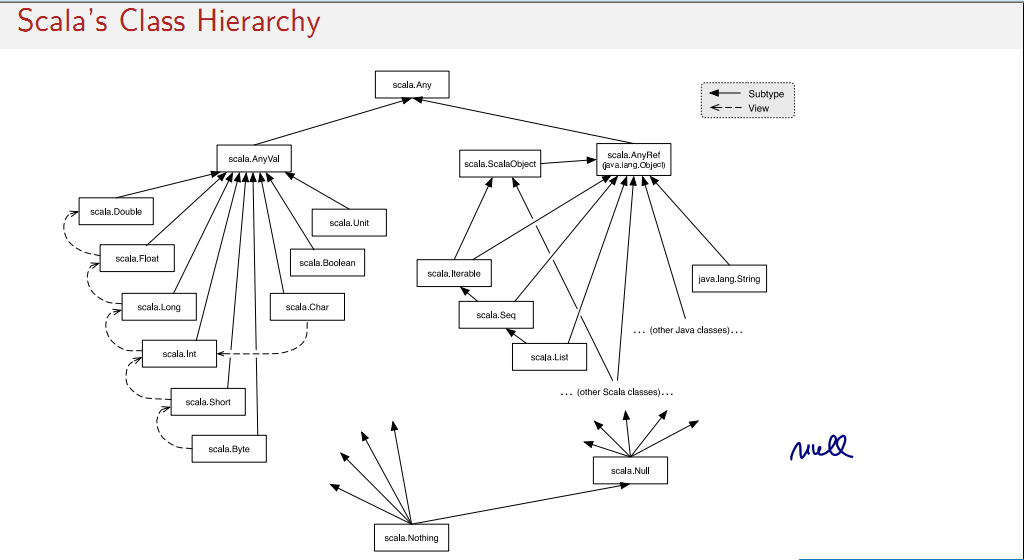

- Top Types in Scala

- Any: the base type of all types, Methods: ‘==‘, ‘!=‘, ‘equals‘, ‘hashCode, ‘toString‘

- AnyRef: The base type of all reference types, Alias of ‘java.lang.Object‘

- AnyVal: The base type of all primitive types

Scala的类型继承关系图:

- Nothing

Nothing is at the bottom of Scala’s type hierarchy. It’s a subtype of every other type. There is no value of type Nothing.

Nothing的两个用途:

- To signal abnormal termination

- As an element type of empty collections (see next session), 例如:Set[Nothing]

def func(): Nothing = throw new Exception("Nothing.")

- Scala.Null

Scala.Null is a subtype of every other type. The type of null is Scala.Null.

- 多态(Polymorphism)

Polymorphism means that a function type comes “in many forms”. In programming it means that:

- the function can be applied to arguments of many types.

- the type can have instances of many types.

Two principal forms of polymorphism:

- subtyping: instances of a subclass can be passed to a base class.

- generics: instances of a function or class are created by type parameterization.

- 参数化(Parametrization): Type parameterization means that classes as well as methods can now have types as parameters.

在Scala中,类和函数都可以拥有泛型参数。

class A[T](ae: T) {

def e = ae

}

def func[T](e: T) = println(e)

- type erasure

Type parameters do not affect evaluation in Scala. We can assume that all type parameters and type arguments are removed before evaluating the program.

- Languages that use type erasure include: Java, Scala, Haskell, ML, OCaml.

- Languages that keep the type parameters around at run time: C++, C#, F#.

Week 4: Types and Pattern Matching

- Functions as Objects

In fact function values are treated as objects in Scala. Functions are objects with apply methods.

例如Scala.Function, Scala.Function1, etc.

package scala

trait Function1[A, B] {

def apply(x: A): B

}

- Expansion of Function Values

匿名函数(Anonymous Function)

(x: Int) => x * x

展开后的形式为:

{

class AnonFun extends Function1[Int, Int] {

def apply(x: Int) = x * x

}

new AnonFun

}

再举一个相关的例子:

import scala.Function1

object progfun {

println("Welcome to the Scala worksheet") //> Welcome to the Scala worksheet

val f = new Function1[Int, Int] {

def apply(x: Int) = x * x

} //> f : Int => Int = <function1>

f.apply(7) //> res0: Int = 49

object One {

def apply() = println("no arg")

def apply(x: Int) = println("one arg")

def apply(x: Int, y: Int) = println("two args")

}

One() //> no arg

One(1) //> one arg

One(1, 2) //> two args

}

-

Function1的定义如下:trait Function1[-T1, +R] extends AnyRef。 -

A pure object-oriented language is one in which every value is an object. If the language is based on classes, this means that the type of each value is a class.

-

在Scala中,任何数据类型都可以用类表达出来。

object progfun {

class Int {

def + (that: Int): Int

def - (that: Int): Int

def * (that: Int): Int

def / (that: Int): Int

// ...

}

}

-

Polymorphism: 多态:两个方面:子类型(Subtyping)、泛型(generics)。

-

Type Bounds and Variance

- Type Bounds: subject the type parameters to sub type constraints.

- Variance: defines how parameterized types behave under sub typing.

-

Generally, the notation

S <: Tmeans: S is a subtype of T. (upper bound)S >: Tmeans: S is a supertype of T, or T is a subtype of S. (lower bound)[S >: T <: R]means: S is a subtype of T, and S is a subtype of R. It would restrict S any type on the interval between T and R. (mixed bound)

-

The Liskov Substitution Principle

Substitutability is a principle in object-oriented programming. It states that, in a computer program, if S is a subtype of T, then objects of type T may be replaced with objects of type S without altering any of the desirable properties of that program (correctness, task performed, etc.). More formally, the Liskov substitution principle (LSP) is a particular definition of a subtyping relation, called (strong) behavioral subtyping, that was initially introduced by Barbara Liskov in a 1987 conference keynote address entitled Data abstraction and hierarchy.

In Scala, If A <: B, then everything one can to do with a value of type B one should also be able to do with a value of type A.

-

Say

C[T]is a parameterized type and A, B are types such thatA <: B. In general, there are three possible relationships between C[A] and C[B]:C[A] <: C[B]: C is covariant(co-variant)C[A] >: C[B]: C is contravariant(contra-variant)- neither C[A] or C[B] is a subtype of the other: C is nonvariant(non-variant)

Scala lets you declare the variance of a type by annotating the type parameter:

class C[+A] { ... }C is covariantclass C[-A] { ... }C is contravariantclass C[A] { ... }C is novariant

- Variance check.

Rules:

- covariant type parameters can only appear in method results.

- contravariant type parameters can only appear in method parameters.

- invariant type parameters can appear anywhere.

A problematic example:

trait List[+T] {

def isEmpty = false

def prepend(elem: T): List[T] = new Cons(elem, this)

}

class Cons[T](val head: T, val tail: List[T]) extends List[T] {

override def isEmpty: Boolean = false

}

object Nil extends List[Nothing] {

override def isEmpty: Boolean = true

}

In function prepend, covariant type parameter T is used in method parameters, then, the compiler will report a error:

covariant type T occurs in contravariant position in type T of value elem

How to correct it, make it variance-correct ? The answer is that use lower bounds:

trait List[+T] {

def isEmpty = false

def prepend[U >: T](elem: U): List[U] = new Cons(elem, this)

}

More, the method prepend violates LSP (Liskov Substitution Principle). If xs is a list of type List[NonEmpty], when we call xs.prepend(Empty), it would lead to a type error. xs.prepend requires a NonEmpty object, and found Empty, but, List[NonEmpty] is also a subtype of List[IntSet]. so, it’s problematic.

We can see that the variance checking rules was actually invented to prevent mutable operations in covariant class, also rules out something which doesn’t involve any mutability at all.

Covariant type parameters may appear in lower bounds of method type parameters, and contravariant type parameters may appear in upper bounds of method.

- Pattern Matching

Pattern Matching is a generalization of switch from C/Java to class hierarchies.

- Match Syntax:

matchis followed by a sequence of cases,pat => expr.- Each case associates an expression expr with a pattern pat.

- A MatchError exception is thrown if no pattern matches the value of the selector.

e match { case p1 => e1 ... case pn => en }

Patterns are constructed from:

- constructors, e.g.

Number,Sum(case class), - variables, e.g. n,

e1,e2, - wildcard patterns

_, Important - constants, e.g.

1,true.

object Progfun {

def func() = {

val d = 1;

d match {

case 1 => "abcd"

case 2 => "efgh"

case _ => "catch default value."

}

}

def main(args: Array[String]) = {

println(func())

}

}

在这个例子中,match匹配到1之后,func函数直接返回"abcd",不会接着运行后面的语句,不需要break。

- Using

case classin Lambda expressions.

Something, we need to construct a complex data structure(link tuple) as Lambda’s parameter, we can use case here:

List(('a', 97), ('b', 98), ('c', 99)) map ({ case (c, i) => println(c + " " + String.valueOf(i)) })

//> a 97

//| b 98

//| c 99

//| res1: List[Unit] = List((), (), ())

If we simply use map((c, i) => println(c + " " + String.valueOf(i))), we will get a error report and suggestion from Scala compiler:

Multiple markers at this line

- missing parameter type

- missing parameter type Note: The expected type requires a one-argument function accepting a 2-Tuple.

Suggestion from compiler:

Consider a pattern matching anonymous function,

{ case (c, i) => ... }

-

How does a case class differ from a normal class?

- You can do pattern matching on it,

- You can construct instances of these classes without using the

newkeyword, - All constructor arguments are accessible from outside using automatically generated accessor functions,

- The

toStringmethod is automatically redefined to print the name of the case class and all its arguments, - The

equalsmethod is automatically redefined to compare two instances of the same case class structurally rather than by identity. - The

hashCodemethod is automatically redefined to use the hashCodes of constructor arguments.

Most of the time you declare a class as a case class because of point 1, i.e. to be able to do pattern matching on its instances. But of course you can also do it because of one of the other points.

Case classes can be seen as plain and immutable data-holding objects that should exclusively depend on their constructor arguments. This functional concept allows us to

- use a compact initialisation syntax (

Node(1, Leaf(2), None)) - decompose them using pattern matching

- have equality comparisons implicitly defined

In combination with inheritance, case classes are used to mimic(模仿) algebraic datatypes.

Week 5: Lists

-

Higher-Order List Functions

-

Map and Filter

-

Equational Proof on Lists

-

List.groupBy

def groupBy[K](f: (A) ⇒ K): Map[K, List[A]]

Partitions this traversable collection into a map of traversable collections according to some discriminator function.

Note: this method is not re-implemented by views. This means when applied to a view it will always force the view and return a new traversable collection.

Example:

object progfun {

"abcd".groupBy(x => x) //> res0: scala.collection.immutable.Map[Char,String] =

//| Map(b -> b, d -> d, a -> a, c -> c)

"abcdaa".groupBy(x => x) //> res0: scala.collection.immutable.Map[Char,String] =

//| Map(b -> b, d -> d, a -> aaa, c -> c)

}

Push all elements which having the same result of f: param => retval to a same group, and build a map (retval -> group). Then, build all maps to a List.

Week 6: Collections

- Generate Pairs

The Law is that:

xs flatMap f = (xs map f).flatten

- The difference between

mapandflatMap: flatMap works applying a function that returns a sequence for each element in the list, and flattening the results into the original list.

For Example:

object progfun {

val x = 1 until 3

def f(x: Int) = List(x-1, x, x+1)

x map (f)

x flatMap f

}

在Scala Worksheet中的运行结果:

res0: [List[Int]] = Vector(List(0, 1, 2), List(1, 2, 3))

res1: [Int] = Vector(0, 1, 2, 1, 2, 3)

- For-Expression

for (p <- persons if p.age > 20) yield p.name

is equivalent to

persons filter (p => p.age > 20) map (p => p.name)

object progfun {

for {

i <- 1 until 4

j <- 1 until i

if i + j < 6

} yield (i, j)

}

的运行结果为:

res0: [(Int, Int)] = Vector((2,1), (3,1), (3,2))

Higher-order functions such as map, flatMap or filter provide powerful constructs for manipulating lists, but sometimes the level of abstraction required by these function make the program difficult to understand.

In this case, Scala’s for expression notation can help.

- Translation of For

The syntax of for is closely related to the higher-order functions map, flatMap and filter. These functions can all be defined in terms of for:

def mapFun[T, U](xs: List[T], f: T => U): List[U] =

for (x <- xs) yield f(x)

def flatMap[T, U](xs: List[T], f: T => Iterable[U]): List[U] =

for (x <- xs; y <- f(x)) yield y

def filter[T](xs: List[T], p: T => Boolean): List[T] =

for (x <- xs if p(x)) yield x

FilterandwithFilter

From the scala docs:

Note: the difference between c filter p and c withFilter p is that the former creates a new collection, whereas the latter only restricts the domain of subsequent map, flatMap, foreach, and withFilter operations.

So filter will take the original collection and produce a new collection, but withFilter will non-strictly (ie. lazily) pass unfiltered values through to later map/flatMap/withFilter calls, saving a second pass through the (filtered) collection. Hence it will be more efficient when passing through to these subsequent method calls.

In fact, withFilter is specifically designed for working with chains of these methods, which is what a for comprehension is de-sugared into. No other methods (such as forall/exists) are required for this, so they have not been added to the FilterMonadic return type of withFilter.

forand database. Similar ideas underly Microsoft’s LINQ.

Week 7: Lazy Evaluation

- Proof the implementations.

What does it mean to prove the correctness of this implementation?

One way to define and show the correctness of an implementation consists of proving the laws that it respects.

(From Martin Odersky’s slides)

- Stream

Streams are similar to lists, but their tail is evaluated only on demand.

lazy val fibs: Stream[Int] = 0 #:: 1 #:: fibs.zip(fibs.tail).map { n => n._1 + n._2 }

fibs take 10 foreach println

Another example:

val nums = Stream.from(1) //> nums : scala.collection.immutable.Stream[Int] = Stream(1, ?)

nums.take(10).toList //> res0: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

This is a common but important way to get a list of integers with variable length.

- Stream Cons Operator

#:: xs == Stream.cons(x, xs)

- Lazy Evaluation

Lazy Evaluation: do thing as late as possible and never do then twice.

The proposed implementation suffers from a serious potential performance problem: If tail is called several times, the corresponding stream will be recomputed each time.

This problem can be avoided by storing the result of the first evaluation of tail and re-using the stored result instead of recomputing tail.

In a purely functional language an expression produces the same result each time it is evaluated.

-

Evaluation Strategies

- lazy evaluation

- by-name evaluation: everything is recomputed

- strict evaluation: normal parameters and

valdefinitions.

-

Infinite Streams

def from(n: Int): Stream[Int] = n #:: from(n+1)

val ints = from(0)

ints take 10 foreach println

- The Sieve of Eratosthenes

The Sieve of Eratosthenes is an ancient technique to calculate prime numbers.

def from(n: Int): Stream[Int] = n #:: from(n+1)

def sieve(s: Stream[Int]): Stream[Int] =

s.head #:: sieve(s.tail filter (_ % s.head != 0))

val primes = sieve(from(2))

- Conclusion

Functional programming provides a coherent set of notations and methods based on

- higher-order functions,

- case classes and pattern matching,

- immutable collections,

- absence of mutable state,

- flexible evaluation strategies:

strict/lazy/by name.

The End

Finish this course. 2015-07-31, at Beihang University.